Buying landscape

Tompkins has been buying property in Patagonia for the last 20 years in order to protect it from the landscape blanchers and the ecology-obsessed from the dams.

How many enlightened hotels in paradisiacal locations don’t suffer nowadays the consequence of the developing approach previous to the Great Recession? How many hotels haven’t sold views without registering them beforehand in the Property Registry? That competitive advantage of some locations above others, apparently free, always found expression in the graphic splendor of a tourism brochure or a webpage with appealing colors, without any more intrinsic cost than having opened a window towards the mountain or tasking the architect with an infinity pool.

There were those, absorbed in the panorama, who believed in paradise thanks to a heavenly image. But the postcard ended up having a price: the requalification of the terrain on behalf of the current mayor, urged to feed the municipal coffers, if not more personal needs. And all without losing sight of the obstacles in tackling regional decentralization – that is to say, municipal autonomy.

Then, when the neighboring property has been requalified and from the ground an entire urbanization has sprouted with townhouses, is when the business laments ensue. “They have stolen my view,” “They have asphyxiated my business,” “They have surrounded the hotel with housing developments, asphalt, noise, garbage, and syringes.”

When this happens, there is no other option left than conveniently valuing the view and… buying it. Buying passage? Why yes: buying mountains, forests, lakes, rivers, sky, and land so no one can steal the views of the hotel – if the business mainly sells to the sensible fibers of the retina, the optic nerve.

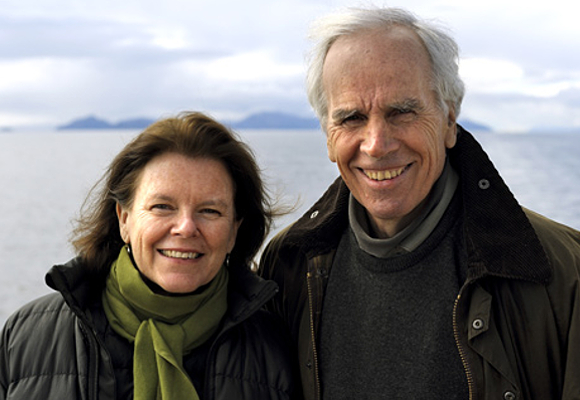

Very sane mad people have been engaged in this endeavor, in numerous countries around the world. But none, perhaps, so much as the North American Douglas Tompkins, who with the power of money and visual acuity (his business nowadays is views) has become public enemy number one of Chile and Argentina, and who is on his way to being so in Paraguay. A multimillionaire from the fashion company Esprit and the creator of North Face, Tompkins resolved to purchase no less than 550,000 hectares in Patagonia, which is equivalent to half the country, or cutting Chile in two, thus protecting this vast austral territory from the voracity of the salmon industries (today ruined by a negotiation that smelled of success), the forest plantations (a second line of companies who operate in the Amazon), and the hydroelectric plants, big multinationals who signed up at the last minute for renewable sources and are enthusiastically supported by ecological movements that dream of a country of windmills and reservoirs in detriment of the more landscape-worthy and efficient nuclear energy.

Tompkins has been buying property in Patagonia for the last 20 years in order to protect it from the landscape blanchers and the ecology-obsessed from the dams. Many of these hectares, which couldn’t fit into the whole of the Basque Country, have been reverted to the Chilean State on the guarantee of promoting a web of national parks in them. Despite this, many Chileans still suspect the praiseworthy intentions of the New York millionaire and repeatedly express their amazement at the fact that a philanthropist can buy so much forest as to leave a country like Chile divided in two. Tompkins is opposed to asphalting the territory, and that puts the brakes on the industrial development of Patagonia, it’s true.

The quixotic act of buying landscapes is incomprehensible even for the official estates of the Andean country, however much their legal system protects private property. The lack of natural protection culture and the national factor – Douglas Tompkins is a foreigner – increases the reservations about this modern Robin Hood of the environment continuing in his effort to obstruct the expropriation of his lands in order to build a coastal road that unites the two sliced portions of the country.

One of his most applauded projects by tourists with a natural sensibility has been the creation of a lodge with only six bedrooms and copper covers, stone claddings, polyurethane panels and mineral wool, furniture made of recycled wood from sheds, and geothermal provisions in the Chacabuco Valley, an impoverished cattle ranch of 78,000 hectares that Tompkins delighted himself in buying to “make a business of the landscape.” He’s set quite an example to follow by the future hoteliers, prevent from the mayors in need of land resources, because there’s no better way of preserving the natural environment than making a business of it.

In fact, other magnate friends of Tompkins, such as the British Joseph Lewis, owner of the Levi’s clothes brand; the North American Ted Turner, founder of CNN; and the Italian Luciano Benetton, the biggest private landowner in Argentina, are buying all the scenery they can.